The Bicycle and the Brain

How a Forgotten Molecule from a Swiss Lab Accidentally Revealed the Secrets of Consciousness

It began with a strange feeling.

On Friday, April 16th, 1943, the Swiss chemist Dr. Albert Hofmann was working in his laboratory at Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in Basel. He was a meticulous man, a scientist dedicated to deconstructing the chemical secrets of medicinal plants. But that afternoon, he was pulled by what he would later call a “peculiar presentiment” toward a compound he had first synthesized and then shelved five years earlier. Its name was lysergic acid diethylamide-25. LSD.¹

He re-synthesized a small amount. As he worked, a peculiar dizziness overcame him. He went home to lie down, and there, with his eyes closed, he was visited by “an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors.”¹ It was a wondrous, if unsettling, two hours. He suspected he must have absorbed a trace amount of the substance through his fingertips.

But how much? And what, exactly, had he stumbled upon? The only way to find out was to conduct an experiment. On himself.

Three days later, he would take a bicycle ride that would change the course of neuroscience forever.

The Alchemist’s Fateful Ride

To call ergot a fungus is an understatement. For centuries, it was a medieval terror. A parasitic growth on rye grain, it was responsible for a horrifying affliction known as St. Anthony’s Fire, which caused burning sensations in the limbs, gangrene, and terrifying hallucinations.² Yet within this dark fungus, Hofmann believed there lay useful medicine. He was searching for a circulatory stimulant, a molecule to help with blood flow. In 1938, the 25th compound he derived in this series—LSD-25—had shown little promise in animal tests and was put away.

Now, on April 19th, 1943, he was sure it held a different kind of power.

Based on similar compounds, he decided a dose of 250 micrograms—a quarter of a milligram, a speck of matter barely visible to the naked eye—would be a safe, threshold amount. At 4:20 PM, he dissolved it in water and drank it. For nearly an hour, nothing. And then, as he noted in his lab journal, the world began to tilt. Dizziness. Anxiety. Visual distortions. Laughter.¹

The bicycle ride home, taken with his lab assistant, became a journey into another dimension. The familiar Basel streets rippled and warped. The ground seemed to breathe beneath his wheels. A neighbor who offered him milk appeared not as a kind woman, but as a “malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.”¹ Back at home, the terror mounted. He feared he was losing his mind, that his own molecule was poisoning him. He called for a doctor. But as the physician found no physical abnormalities, a new feeling began to creep in. The terror subsided, and in its place came a profound sense of wonder. The patterns on the floor pulsed with life. The closed-eye hallucinations returned, this time not as a chaotic stream, but as magnificent, unfolding visions.

Albert Hofmann had just taken the world’s first acid trip. He was the first human to see what this molecule could do. But the next eighty years would be spent trying to understand how it did it.

A Master Key for the Mind’s Lock

What on Earth was happening inside Hofmann’s brain? How could a substance measured in millionths of a gram so completely overhaul the nature of reality?

The answer lies in an act of molecular mimicry.

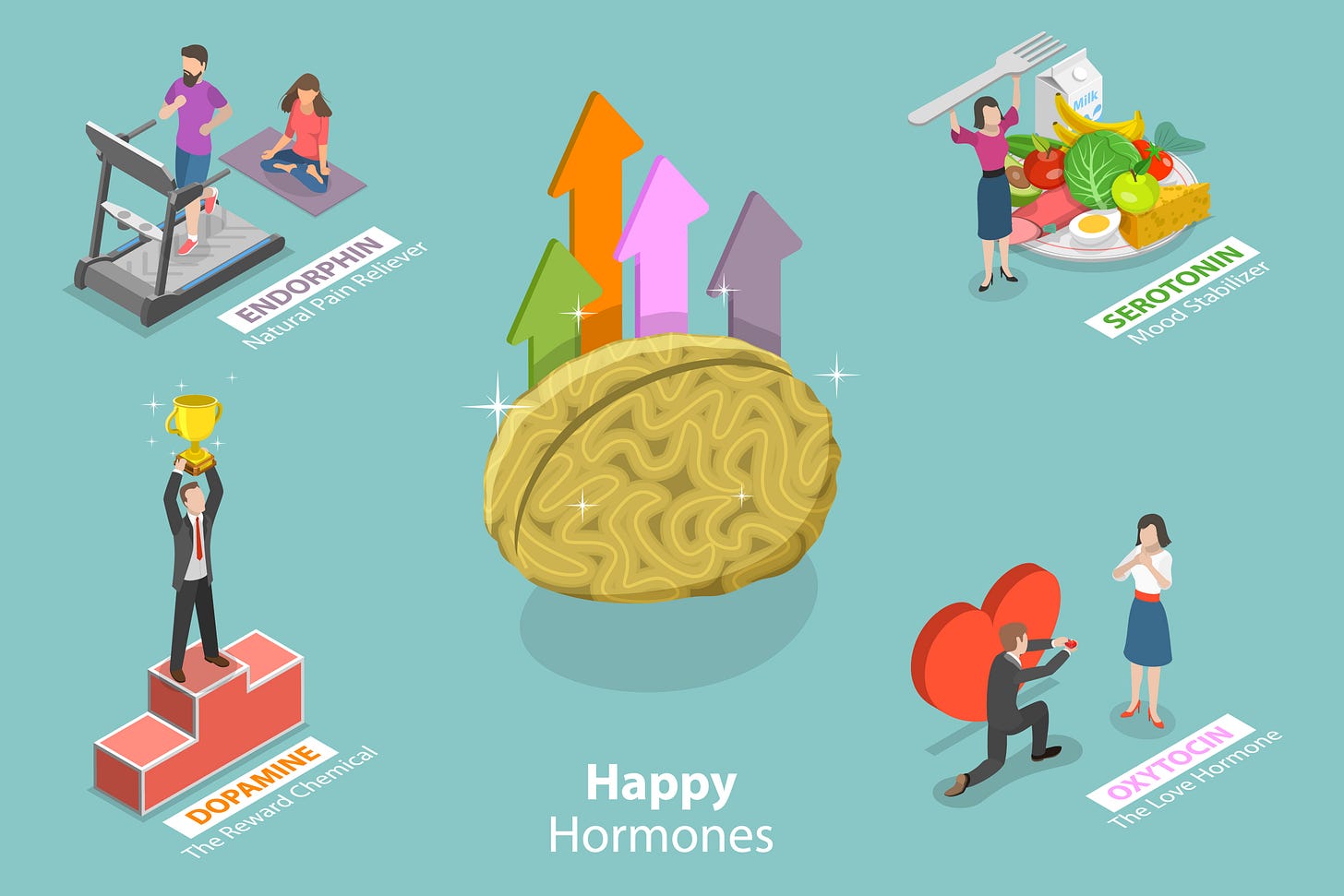

Your brain runs on a constant conversation between neurons, mediated by chemicals called neurotransmitters. One of the most important is serotonin, a molecule that governs nearly everything: your mood, your sleep, your appetite, and crucially, your perception of the world. It’s the brain’s great manager.

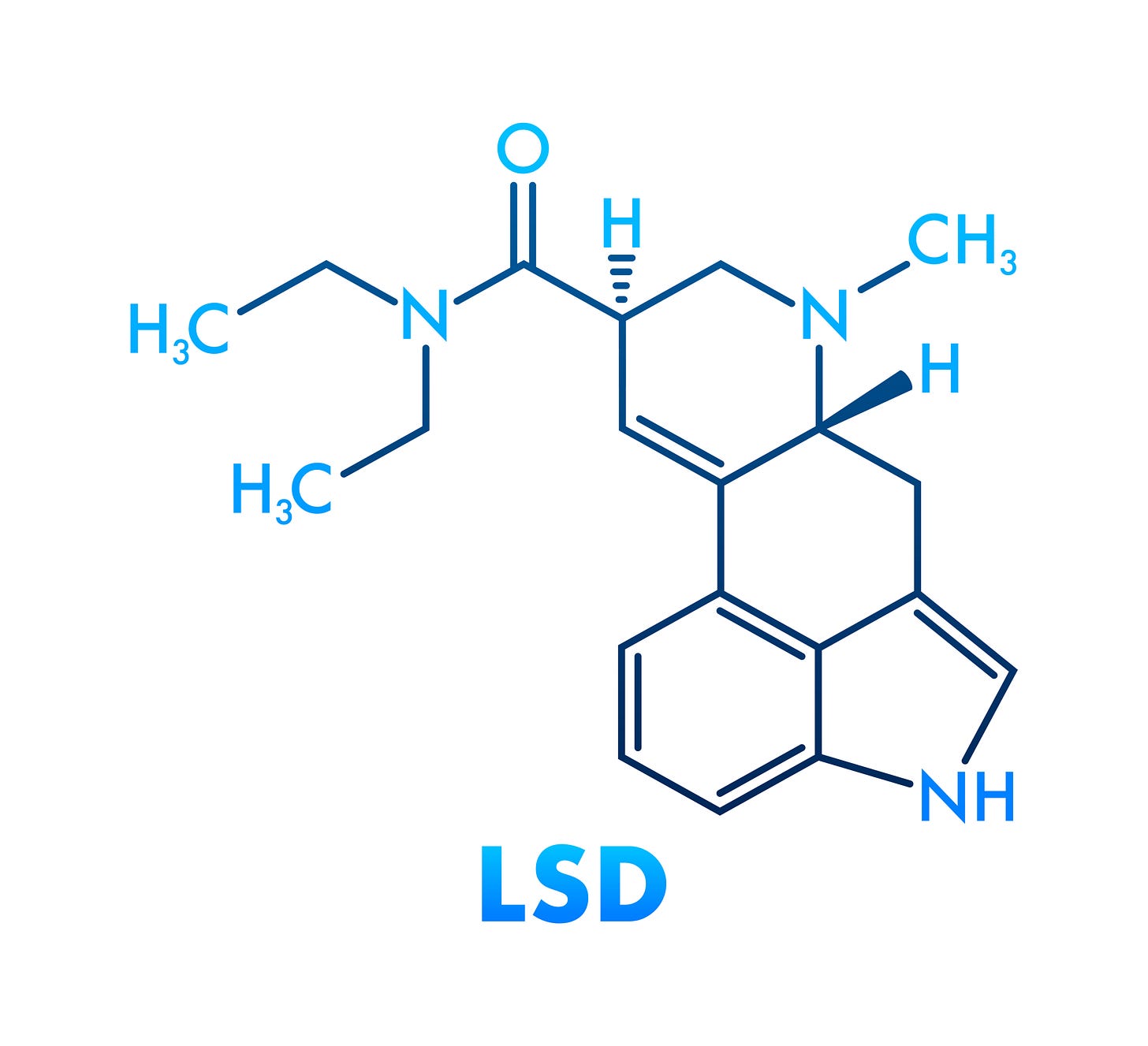

When Hofmann created LSD, he unknowingly sculpted a near-perfect imitation of serotonin. It is a molecular master key, shaped so exquisitely that it can slide into the locks meant for serotonin—specialized proteins on the surface of neurons called receptors.

LSD’s primary target is a very specific lock: the 5-HT2A receptor.³ When this receptor is activated, it changes the way neurons fire and communicate. But LSD doesn’t just fit the lock; it gets stuck. Recent research using cryo-electron microscopy has revealed LSD’s stunning trick: when the molecule slides into the 5-HT2A receptor, a flexible loop of the protein folds over it like a lid, trapping it there for hours.⁴

This “lid-latch” mechanism explains LSD’s incredible potency and long duration. A tiny amount of the molecule can cause a huge and lasting effect because once it’s in, it’s not leaving anytime soon. It’s not just knocking on the door; it’s picking the lock and settling in for the night.

The Symphony of a Dissolving Self

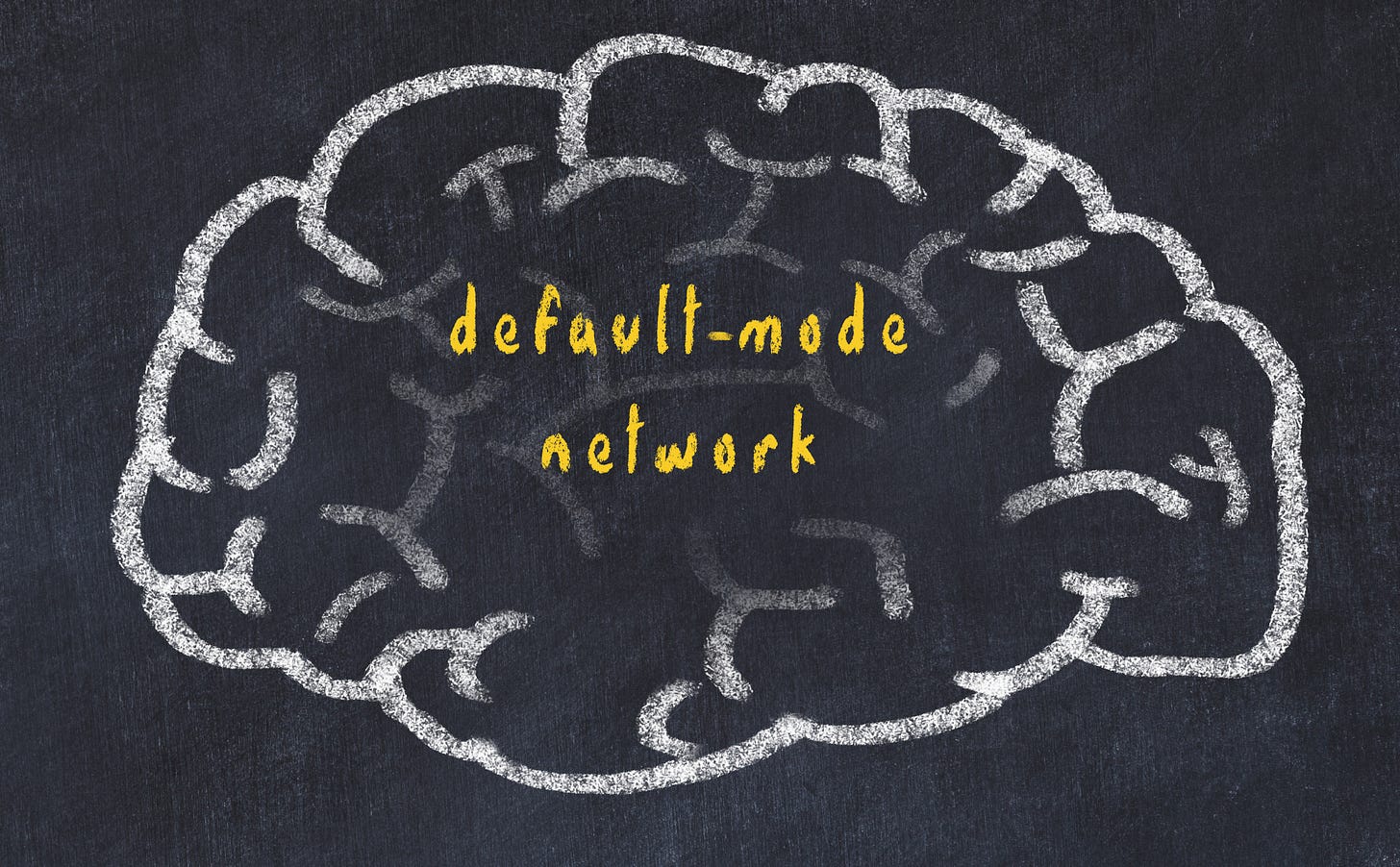

If locking into a single receptor is the cause, what is the effect on the brain as a whole? Imagine your brain’s activity is an orchestra. Day to day, there’s a conductor on the podium, keeping everyone in time, making sure the violins don’t overpower the woodwinds. This conductor is a network of brain regions called the Default Mode Network (DMN).

The DMN is the seat of your ego. It’s the part of you that ruminates about the past, worries about the future, and maintains a stable sense of “I.” It’s the voice in your head.⁵

Modern fMRI scans of brains on LSD show something remarkable: the DMN goes quiet. The conductor leaves the stage.⁶

With the conductor gone, the orchestra begins to improvise. Brain regions that rarely speak to each other suddenly strike up vibrant conversations. The visual cortex starts chattering with the part of the brain responsible for self-awareness. The auditory centers link up with emotional processing hubs. The rigid, segregated structure of the brain dissolves into a more unified, interconnected, and flexible state—a state neuroscientists call a higher “entropy” brain.⁶

This is the neural basis for the psychedelic experience: the "dissolving" of the ego, the blending of senses (seeing sounds, hearing colors), and the profound feeling of being connected to everything. It’s not just chaos; it’s a new kind of harmony.

A Pinprick of Power

It’s difficult to overstate LSD’s potency. An active dose is around 100 micrograms (0.0001 grams). If you took a single packet of sugar (about one gram) and divided it into 10,000 equal piles, just one of those tiny piles would be enough for a standard dose. It is thousands of times more potent by weight than psilocybin (from magic mushrooms) or mescaline (from peyote), making its synthesis in 1938 a truly unique chemical achievement.

From Problem Child to Prodigal Son

Albert Hofmann lived to be 102. He watched his “problem child” escape the lab and ignite a cultural revolution, become a catalyst for both artistic genius and psychological breakdown, and ultimately be outlawed and driven underground. He always maintained that if used responsibly, LSD was a “medicine for the soul.”

Today, science is catching up to Hofmann’s intuition. The very effects that made LSD a cultural threat—the dissolution of the ego and the radical shift in perspective—are now being explored as powerful therapeutic tools. In carefully controlled clinical settings, psychedelic-assisted therapy is showing remarkable promise in FDA-approved trials for treating end-of-life anxiety, PTSD, and severe depression.⁷

The journey that began with a strange feeling and a bicycle ride in Basel is far from over. The molecule born from a medieval fungus has become a key, not just for unlocking altered states, but for understanding the very nature of consciousness itself. It seems Hofmann’s problem child may finally be coming home.

Did You Know?

Before it was a counter-culture icon, the CIA saw LSD as a tool. In the infamous MKUltra project, they tested the drug on citizens, hoping to develop it as a truth serum or mind-control agent.

The word “psychedelic” was born from a poetic exchange. In 1956, psychiatrist Humphry Osmond wrote to author Aldous Huxley, struggling for a word to describe these drugs. Huxley shot back the winning reply: “To fathom Hell or soar angelic, just take a pinch of psychedelic.” The term means “mind-manifesting.”

Psychedelic therapy isn’t new. In the 1950s and 60s, thousands of patients were legally treated with LSD for conditions like alcoholism, with some studies showing remarkable success before research was shut down in the late 60s.

It inspired the pioneers of personal computing. Apple co-founder Steve Jobs called his experience with LSD “one of the most important things in my life,” believing it opened his mind to the kind of innovative thinking that led to the Macintosh.

Explore the Intersection of Molecules & Morals

This story is only the first entry in our ongoing series, Molecules & Morals, where we unlock the stories of the world's most controversial substances. From the poppy that fueled empires to the synthetic powders that redefined warfare, we'll explore the potent chemistry that has shaped our history and our minds.

For Further Reading

LSD: My Problem Child by Albert Hofmann — The definitive, first-hand account of the discovery and the chemist’s lifelong relationship with his creation. (Link is to a free PDF hosted by MAPS).

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan — An accessible and beautifully written exploration of the new science of psychedelics, from LSD to psilocybin.

“The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs” by Carhart-Harris et al. (Frontiers in Human Neuroscience) — For those wanting a deeper scientific dive into the brain imaging studies.

Bibliography

¹ Hofmann, A. (1980). LSD: My Problem Child. McGraw-Hill.

² Eadie, M. J. (2009). Convulsive ergotism: epidemics of the story of St Anthony's fire. The Lancet Neurology, 8(1), 86-92.

³ Nichols, D. E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological reviews, 68(2), 264-355.

⁴ Wacker, D., et al. (2017). Crystal Structure of an LSD-Bound Human Serotonin Receptor. Cell, 168(3), 377-389.e12.

⁵ Raichle, M. E. (2015). The brain's default mode network. Annual review of neuroscience, 38, 433-447.

⁶ Carhart-Harris, R. L., et al. (2016). Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(17), 4853-4858.

⁷ Gasser, P., et al. (2014). LSD-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease: a qualitative study of acute and sustained subjective effects. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(12), 1125-1135.